The Space Race was a little before my time but even today it’s hard to pass beyond middle school without learning its history. From the mid-1950’s through the early ‘70’s, The Space Race was a superpower battle between the USA and the USSR to see who could first land a man on the moon. This whole Space Race spectacle offered one primary benefit: bragging rights. In today’s world that seems so dewy-eyed, doesn’t it? Imagine.. Two nations locked in battle not over economic gain or shipping channels or religion. Rather, they were duking it out to see who could be crowned Most Innovative.

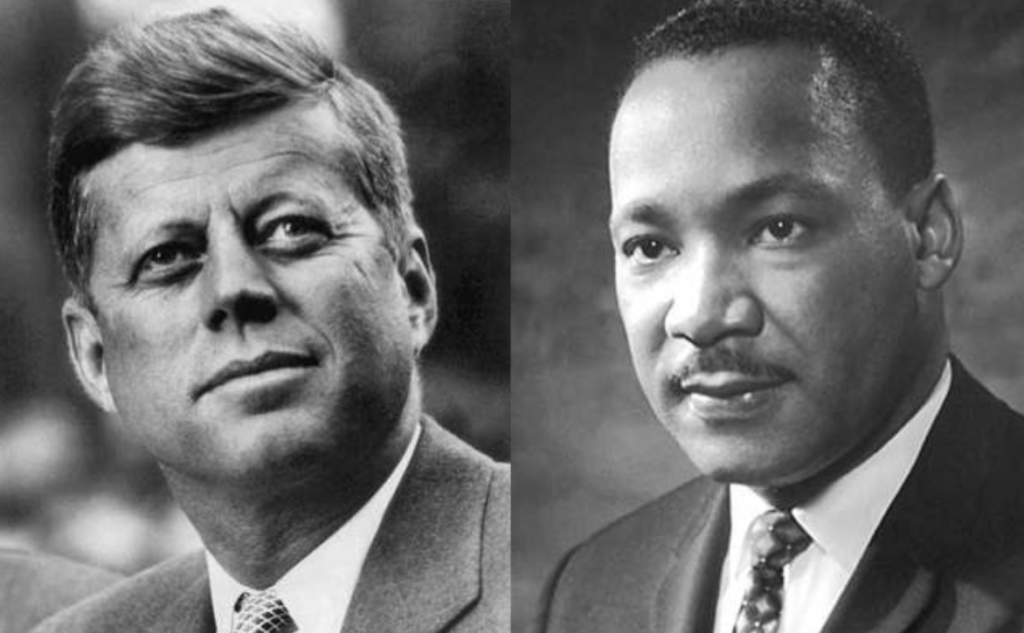

You may also remember from your middle school classes that early in the race, the US was getting its ass kicked. By 1961 the USSR had already celebrated a couple orbital launches while NASA had yet to launch even a bottle rocket. John F. Kennedy, America’s president at the time, was under immense pressure to save face and prove that his nation could keep pace, and little known then to the public, JFK was already filled with shame and embarrassment because the Soviet premier, Nikita Krushchev, had recently met with Kennedy and steamrolled him like a JV football payer on an NFL field. So extreme was the Krushchev-inflicted steamroll that JFK retreated to a dark room, slumped in a chair, pulled a hat over his eyes, and confessed the Krushchev meeting was, “The worst thing in my life.”

Imagine for a moment you’re Kennedy: New to the job, losing the World’s Fanciest Science Fair, trying to guide a NASA team whose space-age engineering language you don’t even understand and appease a public screaming for results all while your inner voice is whispering, “Your number one adversary just pistol whipped you, publicly and privately, and he thinks you’re an idiot.” Not the ideal time to expose yourself to humiliation, but that’s exactly what Kennedy did.

What I didn’t learn until recently was that the Soviets would keep their launch attempts under strict wraps until after they’d had a successful one, at which point they’d broadcast a blind side gut punch press release designed to deflate their adversaries. Kennedy, even while smarting from those announcements, opted for a different approach. He demanded full transparency that, in his eyes, would help the entire nation appreciate its risk. Despite the exposure to his own reputation, JFK wanted the world to know that failure was an option, and that his nation was willing to share the good news and the bad. Kennedy knew what the Soviets back then and, I’d argue, so many of us today don’t: Vulnerability, not staged perfection, earns loyalty.

On February 20, 1962, over 100 million Americans tuned in to NASA’s launch attempt, and I gotta believe every one of them felt an elation that comes only when a moment that could have gone horribly wrong goes wonderfully right. Kennedy, who’d staked his presidential brand on the effort, earned seeds of pride and loyalty that day that inspired the nation’s most talented men and women to join The Space Race and fight for a win. Not for the promise of an IPO or a million Instagram followers or the biggest paycheck (there’s that dewy-eyedness again!), but to be part of something that Kennedy positioned as important, risky, and hard.

The Soviets portrayed themselves as perfect; the Americans portrayed themselves as vulnerable. Hmmmm…. Perfect vs. vulnerable… Which do you think instills trust over skepticism, empathy over jealousy, an instinct to avoid vs. a desire to join? The results speak for themselves. Seven years later NASA’s Mission Control won The Space Race with an average age of – ready for this? – 28.

I wonder if The Space Race would play out the same today. Would our public officials risk public humiliation at a time the adversary is doing victory laps? Would our nation’s best and brightest toss aside big paychecks and stock options to join a publicly funded, underdog fight? I once read about a Silicon Valley executive who said, “Our best engineers used to crack the code on how to put a man on the moon. Now they write code trying to get people to click on social media ads.” I haven’t reached that level of cynicism but I have concluded that Kennedy’s approach is still the right one to follow. Your best opportunities to win the hearts and minds of your target audience come when you declare a bold goal, share unflinchingly the stakes of missing it, and do so with humility and vulnerability.

On today, Martin Luther King Jr. Day, what’s your dream? How openly are you sharing your dream and why it’s important, even if failure to reach it leaves you vulnerable to ridicule? Speaking of vulnerability, it’s interesting to note that MLK’s “I have a dream” speech was not part of the script he planned to deliver that day in August 1963. It was only when he, like Kennedy, veered from the safe path and went off script that he truly won his audience. Proof that King’s message resonated? Immediately following his speech in front of the Lincoln Memorial, MLK headed to The White House where JFK, having exclaimed, “He’s damn good. Damn good!” upon watching it on TV, approached King, shook his hand, and said, “I have a dream.”

JFK and MLK: Two leaders who shaped a nation and inspired millions to see themselves in a different light, and whose example I trust we’ll all continue to follow.

Here’s to your dreams, your failures, and your victories. May the mission you choose be important, risky, and hard. Happy MLK Day!

**Special Thank You to Mark Updegrove and his outstanding book, “Incomparable Grace: JFK in the Presidency“, for introducing me through such gifted storytelling to these events and others.